BEEF-STEAK!

We were in Rome for New Year’s and taught to say buon anno, which we repeated like parrots for the next week. By the end of our stay, it had become something like bananooooo and has remained in our lexicon. If the idea of massacring Italian to the point of nonsense strikes you as too-silly, I invite you to consider the Florentine steak, the Bistecca alla fiorentina.

Pellegrino Artusi, in his 1891 cooking manual Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well tells us that it comes “From beef-steak, an English word that is worth the rib of an ox, came the name of our steak, which is nothing more than a chop with its bone, a finger or a finger and a half thick, cut from the sirloin of a steer".

To explain this, we are told the hard-to-verify story that, at the marriage of the Duke of Florence’s daughter in 1565, the English there — on their grand tour — shouted “beef-steak!” over and over at the sight of an ox being roasted in the middle of San Lorenzo. I know many Englishmen who would do the same now.

A moveable feast

I gave up drinking on Shrove Tuesday, the day before Lent, and have decided to mark each year of not drinking on this moveable feast. I love ceremony, and just as the church co-opted pagan rites to build their own, I shall do the same to the church.

I’m writing something about personal ritual, and it would be amazing to get some examples from the readers of Greed. Reply to this email!

Authorship

I have been thinking about the idea of authorship recently. My friend Dina told me that Osip Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda Mandelstam, also a poet, learned to remember his poems, which he preferred to compose while taking long walks so that she could recount them to him when he was at a desk. It did not occur to me then, but does now, that in doing this she must have written — mistakenly or not — a great deal of his work.

I have been thinking about the way (mostly male) authors are given the time to write, and how often this relies on the labour and sacrifice of (mostly female) others. A recent review of Jonathan Sumption’s final book on the 100 Years War begins

There can be no doubt about the scale of Jonathan Sumption’s achievement in his history of the Hundred Years War. Five massive volumes, published between 1990 and this year, each more than six hundred pages of narrative and notes. Together, they total nearly four thousand pages, not counting the bibliographies, with their ever-expanding lists of secondary contributions as well as primary sources in Latin, French, Middle English, Dutch, Catalan and Portuguese. And all this done in Sumption’s spare time from his work as a barrister and then a justice of the UK Supreme Court.

Sumption writes beautifully, and I will stop to listen when he comes on the radio, but this praise made me think that he must never have washed up or hoovered. I think the world would be a kinder place if the labour underpinning so much mind work was properly recognised, that such labour should not be discounted as pointless. A well-rounded individual does do the washing up and someone who does not, does not know life.

I’m writing something longer about this, and wonder if any of you lot have good examples of authors who wrote a great deal because they were pampered by their wives, mothers or servants? I’m thinking of Flaubert having food brought to him by his mother as he dithered for weeks over a single sentence.

1. Since the boom in delivery apps, it would be wrong to ignore the part of very poorly paid male workers, and their ethnic and class position.

Some good things

This weekend I re-acquainted myself with the little schoolyard market beside a busier and more famous market, whose name I will reveal below, to those who pay. I first started visiting when I was twenty or so and it remains the same. Scruffy, like a small market in Devon rather than a tarted-up farmers market in London, with four or five stalls, one selling vegetables from a Kent farm, one selling eggs and meat, one selling oysters and one selling bread.

I, and many others, have written before about the pleasure of seasonality, but will stress it again. Seasonal food is cheaper and better than imported food, though this fact is not always reflected in supermarkets. Moreover, the restrictions it imposes force one to cook more interestingly - no great cuisine emerged from overabundance, something that 20th-century American cooking illustrates aptly.

I bought two wet garlic cloves, four red onions, two cauliflowers, three punnets of beautiful pears, a punnet of cooking apples, five leeks and two punnets of shallots for £15, getting a couple of deals because it was the end of their day and I am very chatty. After, I have a hilarious cycle home laden with blue bags full of vegetables, worrying they’d break.

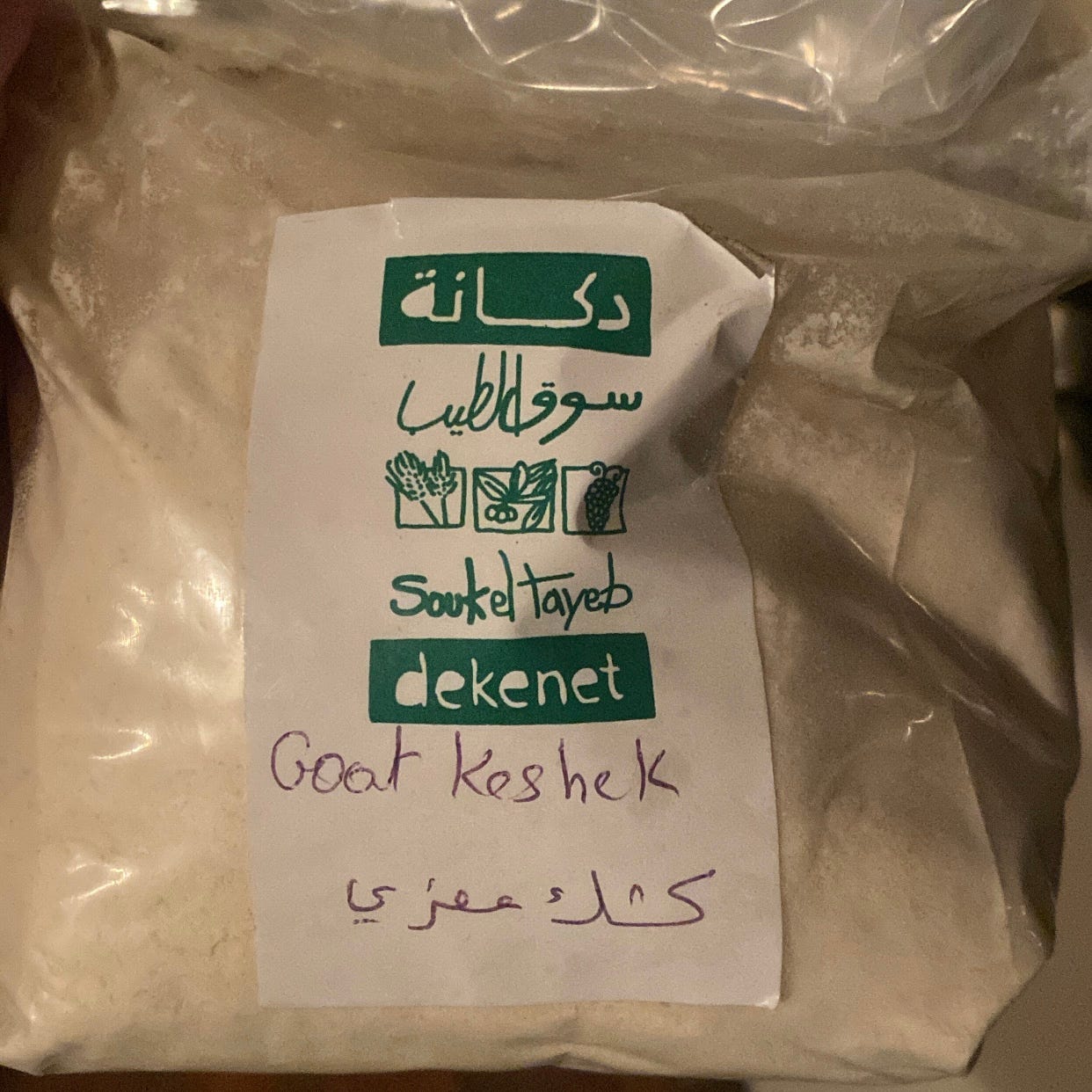

Goat Keshek

We had a Lebanese friend of ours, Laet, to dinner on Sunday, and she came bearing gifts: unprocessed olive oil, sumac and keshek, a yellowish powder in a plastic bag. She’d bought everything at the farmers market from low-intervention producers and so the labels were handwritten, the Latin script curved like the Arabic.

Keshek is made from bulgar and milk, either goat or cow, milled and fermented. It is prepared at the end of summer as a winter provision, most especially by those living in the mountains. To make it we cooked garlic in plenty of olive oil - halved, not minced - until golden. We then added two heaped t-spoons of the keshek, dragged it in the oil and added a cup or so of water. Mixed now and then with a spoon, it soon turned into a thin porridge. Into the bowl it went, Laet then splashed it with the oil (‘like a Lebanese grandma, putting more than you need!’) and it was ready. We passed the bowl around the five of us, each taking a couple of spoonfuls and exclaiming at the deliciousness. It has a mild taste, with a touch of sourness, and is comforting in a deeply childish way.

One can add minced lamb, cooked potatoes, and I am sure other things, but I like it plain, with its hint of garlic. The garlic can be chopped to your preferences — Laet does not like finding the little bits of garlic in hers, so this is how her entire family make it. Keshek reminds me of tarhana, grain and fermented milk or yoghurt found in Central Asia, the Mediterranean and the Middle East, which is an obvious relative.

If you have any knowledge of dried soup mixes — not stocks — made to stretch over the hungry months, please tell me by replying to this email.

A rough list of the best things I’ve eaten this month that I did not cook

Faggots in sage broth at Rochel Canteen

A massive steak and chips at Café Cecilia

Deep fried vegan ice cream at Sen Viet, Kingsland Road

Pyscis Smoked Sprats

A plate of bananas, brown toast and applesauce

Bosc pears from Kent

Biang Biang noodles at Master Wei Xian

A ‘raw’ chocolate bar from Tesco

A recipe for Lamb with Honey and another for Rosemary Custard behind the paywall below

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Greed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.